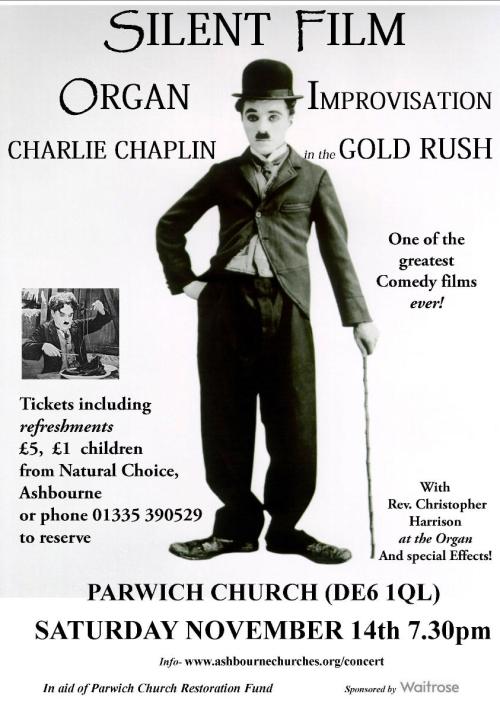

Charles Chaplin made The Gold Rush (1925) out of the most unlikely sources for comedy. The idea came to him when he was viewing pictures of the 1896 Klondike gold rush, and was struck by the image of an endless line of prospectors snaking up the Chilkoot Pass, the gateway to the gold fields. He also happened to read a book about the Donner Party Disaster of 1846, when a party of immigrants, snowbound in the Sierra Nevada, were reduced to eating their own moccasins and the corpses of their dead comrades.

Chaplin – proving his belief that tragedy and ridicule are never far apart – set out to transform these tales of privation and horror into a comedy. He decided that his familiar tramp figure should become a gold prospector, joining the mass of brave optimists to face all the hazards of cold, starvation, solitude, and the occasional incursion of a grizzly bear.

Searching for a new leading lady, he rediscovered Lillita MacMurray, whom he had employed, as a pretty 12-year-old, in The Kid. Still not yet sixteen, Lillita was put under contract and re-named Lita Grey. Chaplin quickly embarked on a clandestine affair with her; and when the film was six months into shooting, Lita discovered she was pregnant. Chaplin found himself forced into a marriage which brought misery to both partners, though it produced two sons, Charles Jr and Sydney Chaplin.

As a result of these events, the production was shut down for three months. Lita was replaced on the film by an enchanting new leading lady, Georgia Hale. Georgia, then 24, had arrived in Hollywood after winning a beauty contest in Chicago and worked as an extra

For two weeks the unit shot on location at Truckee in the snow country of the Sierra Nevada. Here Chaplin faithfully recreated the historic image of the prospectors struggling up the Chilkoot Pass. Six hundred extras, many drawn from the vagrants and derelicts of Sacramento, were brought by train, to clamber up the 2300-feet pass dug through the mountain snow.

For the main shooting the unit returned to the Hollywood studio, where a remarkably convincing miniature mountain range was created out of timber (a quarter of a million feet, it was reported), chicken wire, burlap, plaster, salt and flour. The spectacle of this Alaskan snowscape improbably glistening under the baking Californian summer sun drew crowds of sightseers.

In addition, the studio technicians devised exquisite models to produce the special effects which Chaplin demanded, like the miners’ hut which is blown by the tempest to teeter on the edge of a precipice, for one of the cinema’s most sustained sequences of comic suspense. Often it is impossible to detect the shift from model to full-size set.

Further information about the film at:

A short clip from the film:

Oh deep joy this will take me back to saturday mornings when I was considerably younger[I am 45] dare anyone else own up to watching Chaplin ,Laurel+Hardy before the cartoons came on!!!!!

I’m 44 so that’s way before my time.

Being of a more mature age, 46, I recall being packed off to New Mills Arts Theatre with sixpence on a Saturday morning (then was the local fleapit) to watch Dr. Who, Laurel and Hardy, and cowboy films…….. but then everything got all modern (I blame glam rock and The Wombles), and we got a colour telly, and it was all Swap Shop and stuff. Kinda missed the Charlie Chaplin experience.

Lynne – me and Buntingo could talk you through the whole 1970’s thing if you like…..

When I was doing my post grad art degree in the 60’s ( oh what a time) we had an entire season watching all the old Charlie Chaplin films – partnered by soft porn movies. They became something of a cult evening with full attendance!

We risk getting a whole new customer base for the blog with phrases like “soft porn” in the comments.

Good job I toned it down then!